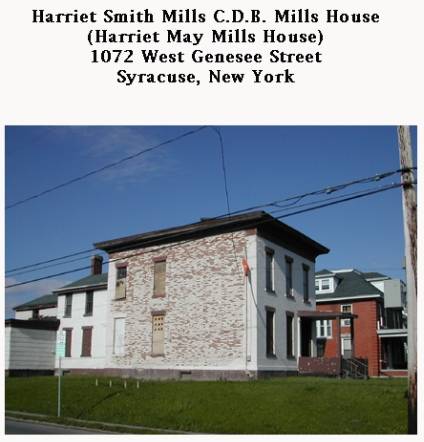

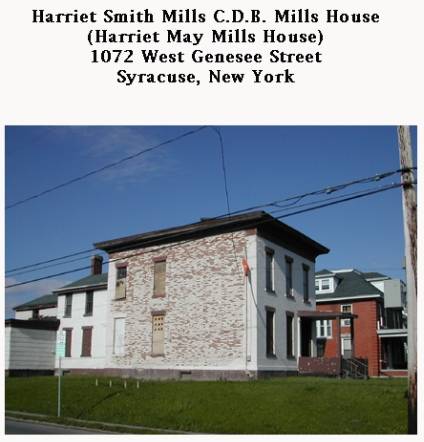

Harriet and C.D.B. Mills House

(Harriet May Mills House)

1072 West Genesee Street

Syracuse, New York

1858

This house, constructed in 1857 for Harriett and C.D.B. Mills, represents European Americans committed to abolitionist activism. It also illustrates the close relationship between abolitionism and the early woman’s rights movement.

From the time they moved to Syracuse in 1852, Harriet Smith Mills (1826-1928) and Charles.De Berard Mills (1821-1900) made this house a gathering place for nationally-known radical abolitionists, temperance reformers, and woman’s rights activists. According to obituaries, reformers such as William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and Lucretia Mott stayed at this house. Obituaries and twentieth century newspaper articles also suggest that the Mills family used their home as a safe house on the underground railroad. (“Death of C.D.B. Mills, Evening Herald, May 15, 1900; “Stop on ‘Underground,’” Post-Standard, October 21, 1930)

C.D.B. Mills was born in New Hartford, New York in 1821. His father was a reform-minded Presbyterian minister, and he sent C.D.B. to Oneida Institute, an abolitionist school open to both blacks and whites. From there, Mills went to Lane Seminary in Ohio, a school wracked by splits over abolitionism, where he studied Oriental languages (including Arabic) and culture. As an adult, he lectured and wrote on Oriental thought, including Buddhism.

From Lane Seminary, he returned to New York State to teach at Sherburne Academy in 1843. Ousted for his anti-slavery views, he opened a private school and then went to Ohio, this time as a minister. Again rejected for his anti-slavery activism, he started a private school in Elyria, Ohio, before moving to Syracuse in 1852. (“Death of C.D.B. Mills, Evening Herald, May 15, 1900)

Harriet Smith Mills had attended Oberlin College, an abolitionist college in Ohio, She married C.D.B. Mills in 1845 and traveled with him to Elyria, Ohio, where they lived from 1846 to 1851 and where, according to a 1927 newspaper article celebrating Mrs. Mills 101st birthday, their home was a stop on the underground railroad. When they moved to Syracuse in 1852, Harriet Mills immediately became active in abolitionism. (New York Herald Tribune, February 13, 1927)

In speech in 1912 for a celebration of the rescue of William “Jerry” Henry, Harriet Mills recalled that

my earliest memory of any important happening here was that of the celebration of the Jerry Rescue. It was held in the round engine house of the Central Railroad in the West End, which was just finished and not yet occupied. I walked there, leading my little baby boy, from the corner of Railroad and Lemon Streets, followin the track so as not to lose my way, as I had been but a few days in the city.

There was a large audience gathered that sat (on rough board seats—not chairs) throughout the afternoon and listened to most stirring appeals for freedom and condemnation of the Fugitive Slave Law. Mr. May, Gerrit Smith, Lucretia Mott and others spoke. Most impressive of all to me was the able, clear, concise, logical address of Lucretia Mott.

(Sperry, 58-59)

Harriet Smith Mills also remembered the Sunday afternoon meetings in City Hall, bringing together ministers and congregations from many different churches to discuss major issues of the day. “It seemed to me the ideal way of seeking truth,” she recalled, “this of marking the different phases of its manifestation through the individual, as no one has the whole truth, and from on one is it fully hidden.” (Sperry, 58-59)

Harriet Smith Mills also attended (or tried to attend) a January 1861 abolitionist lecture scheduled for Convention Hall. It had been organized by Rev. Samuel J. May was to feature Susan B. Anthony and others. :When we gathered at the door of the hall,” remembered Mills,

we found it packed with the mob, not a vacant seat, and their chairman was just going onto the platform. Two or three of our speakers also walked up there, but after looking into those desperate faces and seeing one man handling a pistol in his pocket, and hearing their threats, they came down and joined us at the door again. Dr. Pease invited us to his home, where we spent the afternoon, heard Mr. May, Gerrit Smith, Beriah Green, Parker Pillsbury and Susan Anthony talk, and passed resolutions. (Sperry, 58-9)

That evening, a mob burned Susan B. Anthony and Samuel J. May in effigy on Hanover Square.

Harriet Smith Mills continued her work for equality by actively supporting the woman’s rights movement. In 1917, when she was ninety-one years old, she spoke at a meeting in the Onondaga County Court House to celebrate victory for woman suffrage in New York State. Three years later, she voted for her own daughter, Harriet May Mills, for Secretary of State, the first woman to run for state office in New York State. (“A Century of Memories,” New York Herald Tribune, February 12, 1928)

C.D.B. Mills and Harriet Smith Mills had two children, William Mills (b. 1851) and Harriet May Mills (born in 1857 and named after Samuel J. May). Harriet May Mills graduated from Cornell University in 1879 and soon after, influenced by Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone, she began active work in the campaign for woman’s suffrage. In 1892, she founded the Political Equality Club in Syracuse, which hosted a convention that year. So pleased was Susan B. Anthony with the success of this meeting that she wrote to Mills and her co-worker, Isabel Howland, “I am too proud of you two to keep still—So here goes my heart full of love and rejoicing over my two new young girls in Syracuse. (Watrous, 3)

In the 1890s, she became a major organizer and lecturer for the national woman’s suffrage movement, traveling to California in 1896 to agitate for passage of a suffrage amendment there. Her home became the headquarters of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association, and, in 1910, she was elected President of the state-wide organization. In 1920, she ran for Secretary of State in New York, the first woman to run for state-wide office. Woman’s Building at the New York State Fair was named after her in 1934. She died in 1935. (New York Herald Tribune, February 12, 1920; Watrous)

The Mills family purchased this site on August 14, 1858, and built this house shortly thereafter. The house is a simple Italianate three-bay structure with a two-bay wing on the east side and brackets under the eaves. It stands at the corner of Liberty and West Genesee Streets. Once surrounded by other residences, the house has stood since the 1920s in a neighborhood dominated by car dealers.

The Mills family lived here until Harriet May Mills’ death in 1935, when it was used as the headquarters of G.B. Stringer hardware. In 2001, Syracuse Brick House, with the assistance of the Preservation Association of Central New York, purchased the Mills house for use as a halfway house for women who are recovering from substance abuse. Funding for restoration will come from state, local, and private sources. (New York Preservation, 2001)

Crawford, Beth. Rescuing Harriet May Mills’ Legacy in Syracuse.” The

Landmarker (Fall 2000).

Kirst, Sean. “Disregard of legacies haunts city.” Post-Standard, July 7, 2000.

“Syracuse Suffragist’s Home to be Halfway House,” New York Preservation

(2001)

“Project Report: Preservation and Development of the Harriet May Mills

House.” [2001]

Sperry, Earl. The Jerry Rescue. Syracuse: Onondaga Historical Association,

1924.

Watrous, Hilda R. Harriet May Mills, 1857-1935: A Biography. Syracuse: New

York State Fair, 1984.

Newspaper articles, as noted in text, courtesy of Beth Crawford. Thanks to Beth

Crawford for sharing results of her research.

Local tradition, published during Harriet Smith Mills’ lifetime, suggests that this house was used as a stop on the underground railroad. Most important for this project will be to uncover evidence dating from the Civil War or before to confirm this. Such evidence might come from newspaper sources, especially anti-slavery newspapers. Manuscript censuses might also reveal the presence of African Americans in this household in 1860, 1865, or 1870. Unitarian Church records might also be useful. We know very little about C.D.B. Mills’ employment during the 1850s.